The year the signal was buried

Between 1981–82, an Atari‑based program known as WPA (World Pirate Association) staged a believable underground: terse prompts, denial loops, and a text marketplace that felt operational. The experience converted phone wiring into a place—and that was inconvenient for neat origin stories. The safer public narrative kept research networks tidy and pushed messy homegrown reality offstage.

What the targeted user actually experienced

- The call came to you. A late‑night ring, then the unmistakable modem handshake. This wasn’t dialing into a BBS; the system called first.

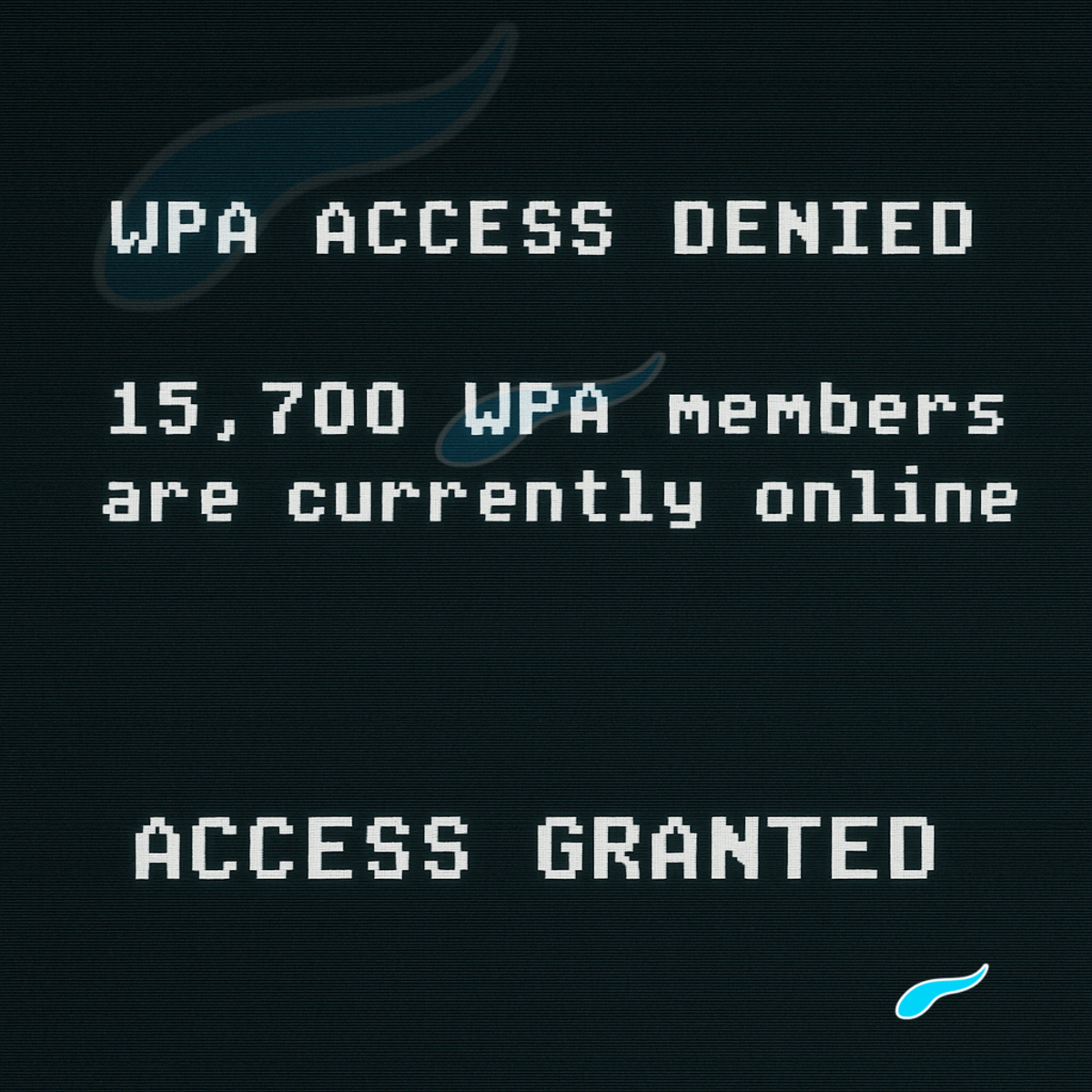

- The gate played hard to get. A minimal terminal demanded

HANDLEandPASSWORD. After several wrong tries the script forced an ACCESS GRANTED—training the visitor to feel like a successful intruder while the sysop observed. - The room felt live. Menus listed contraband, escrow‑style exchanges, and status messages—text only, but steered in real time by the operator. It read like a criminal market; it ran like a simulation; it felt true.

Design note: the denied → denied → granted cadence was intentional. It manufactured confidence while preserving sysop control.

Why monitor instead of arrest?

The operator was a minor. The line was a single household circuit. Given those facts, the rational play was surveillance: capture transcripts, map who picked up, and observe the evolving script. Quiet monitoring preserved the feed; public action would have destroyed evidence and telegraphed methods.

How this disappears from “official” histories

- Liability optics: acknowledging a child‑run, fbi‑monitored simulation of a criminal market raises uncomfortable questions.

- IP harvesting: once narrative pieces leaked into film and media, attribution became reputationally expensive—so the origin was never revealed.

Why it matters

WPA wasn’t a footnote. It was the inflection point where a phone line became a convincing online marketplace—years before the Web. The design pattern (invite‑only dial‑out, denial ramp, forced grant, operator steering) anticipates the modern internet’s psychology of access and reward.

When denial becomes the tell, proceed to the following link: §§ 1961–1968